Questionnaire Design

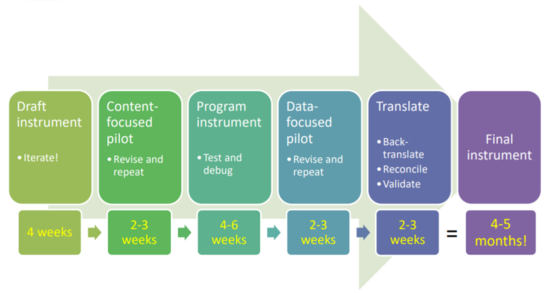

Questionnaire design is the first step in primary data collection. A well-designed questionnaire requires planning, literature reviews of questionnaires, structured modules, and careful consideration of outcomes to measure. Questionnaire design involves multiple steps - drafting, content-focused pilot, programming, data-focused pilot, and translation. This process can take 4-5 months from start to finish, and so the impact evaluation team (or research team) must allocate sufficient time for each step.

Read First

- The drafting stage should align the survey instrument (or questionnaire) with the key research questions and indicators.

- Carefully review existing survey instruments that cover similar topics before starting.

- Divide the questionnaire into modules - this makes it easier to structure the instrument.

- Think through measurement challenges during questionnaire design.

- To avoid recall bias, use objective indicators as much as possible.

- Recall bias is a type of error that occurs when participants are not able to accurately remember past events.

Process and Timeline

The figure below highlights the steps involved in questionnaire design, along with the time that the research team should allocate to each step. The entire process can take 4-5 months.

Draft Instrument

This is the first step in the questionnaire design process. This section describes the various guidelines and aspects of drafting a survey instrument. As a general rule, the questionnaire must always begin with an informed consent form. The remote or field survey can start only after a survey participant agrees to participate. The research team should consider the following while drafting a survey instrument :

- Divide the instrument into modules.

- Perform a literature review of existing instruments.

Modules

In the drafting stage, it is helpful for the research team to start by outlining the various modules that they want to include in the instrument. Follow these steps to structure the modules:

- Theory of Change. Start by drafting and reviewing a theory of change, and prepare a pre-analysis plan. Use the inputs from the members of the research team for this step.

- Outline. Based on the theory of change and pre-analyis plan, prepare an outline of questionnaire modules. The modules should align with the key research questions. Take feedback from the other members of the research team.

- Outcomes of interest. Then, for each module, make a list of all intermediary and final outcomes of interest, as well as important indicators to measure. Again, take inputs from members of the research team, as well as other implementing partners who have prior experience in preparing survey instruments.

- Relevance and looping. Based on this list, discuss relevance and looping for each module. For example, for a survey on households, relevance means asking if a particular module applies to all households. Looping means considering if the questions within a module should be asked to all members in the household.

- Questions. Finally, discuss and draft questions for each module. Do not start from scratch, even if the instrument is for a baseline survey (or first round).

Literature Review

When drafting questions for each of the modules in an instrument, do not start from scratch. Follow these steps to draft the questions:

- Literature review. Start by performing a literature review of existing, reliable, and well-tested questionnaires. Examples of such questionnaires include field or remote surveys in the same country (regardless of the sector), or in the same sector (regardless of the country).

- Compile. Use this review to compile a repository or bank of relevant questions for each module.

- Cite source. In the draft version, add a separate column to note the source of each question. Again, take feedback from the other members of the research team and implementing partners.

You can consult the following resources for the literature review:

- World Bank microdata catalogue

- J-PAL microdata catalogue

- Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) microdata catalogue

- IFPRI microdata catalogue

- International Household Survey Network (IHSN) survey catalogue

Note: While drafting the instrument, it is also important to keep in mind that certain indicators can be hard to measure. This can lead to certain measurement challenges.

Challenges to Measurement

Measurement challenges arise when certain indicators that are important to answer key research questions are hard to measure. It is important for the research team to discuss these, and find a way to resolve these challenges. The following are some of the challenges to measurement, along with suggestions to resolve them.

Nuanced definitions

In some cases, questions which seem straightforward can actually be quite nuanced or complex. Consider the following examples:

- Example 1. While questions about household size seem straight-forward, the answer can differ depending on which definition of household member is used. Without any further clarification, household member can include one, or all of the following - anyone currently living in the household, anyone who has lived more than 6 of the last 12 months in the household, domestic workers, children who are studying in another location but are economically dependent on the household, and adults who live in another location but send monthly remittances.

- Example 2. While it may seem that all respondents should know their age, age can be difficult to measure if respondents do not have birth certificates, do not know their birth year, or are innumerate

To deal with such cases, the research team can take the following steps:

- Pay careful attention during the survey pilot, and identify questions that may be hard to understand for the respondent.

- Adjust the questionnaire accordingly, and train enumerators to resolve these concerns.

- Change the wording of the questions so the meaning is clear, and include definitions within the questionnaire where necessary to make sure all respondents have the same information at the time of answering a question.

Recall bias

When asking survey respondents to recall or estimate information (i.e. income in the last year, consumption last week, plot size, amount deposited in bank account last month), be aware of recall bias.

To avoid recall bias, use objective indicators as much as possible. For example, rather than asking a respondent the size of her agricultural plot, it is better to measure the plot area directly using GPS devices. Rather than asking a respondent how many times she deposited money in her bank account last month, it is better to acquire administrative bank data for accuracy. However, objective measures are often more expensive and may not always be possible. In these cases, make use of internal consistency checks, multiple measurements, and contextual references to ensure high quality data.

Sensitive Topics

For certain topics perceived as socially undesirable (i.e. drug/alcohol use, sexual practice,s violent behaviors, criminal activities), respondents may have incentives to conceal the truth due to taboos or social pressure. This can create bias, the size and direction of which can be hard to predict. To avoid this, enumerators should guarantee anonymity and confidentiality during the informed consent section. Further, survey protocols should guarantee privacy and maximize trust. Consider asking the question in third person, framing the questions to avoid social desirability bias or even possibly allowing respondents to self-administer certain modules. Note that experimental methods such as randomized response technique, list experiments and endorsement experiments can also help elicit accurate data on sensitive topics.

Abstract concepts

Abstract concepts such as empowerment, risk aversion, social cohesion or trust may be defined differently across cultures and/or may not translate well. To measure abstract concepts, first define the concept, then choose the outcome you will use to measure that concept, and finally design a good measure for that outcome. Pilot the question and measurement well.

Outcomes Not Directly Observable

For outcomes not directly observable (i.e. corruption, quality of care), audit studies can help elicit accurate data. In general, it is always best to directly measure outcomes when possible. As a basic example, consider the following example of measuring literacy:

- "Can you read?" Answer choices: yes, no

- "Can you please read me this sentence?" [Enumerators holds up card with a sentence written in the local language]. Answer choices: read sentence correctly, read sentence with some errors, unable to read sentence.

The second option, a more objective measure, is always preferable.

Content-focused Pilot

Program Instrument

Data-focused Pilot

Translate Instrument

Finalize Instrument

Guidelines

- Begin the questionnaire with an

- Identify each survey respondent and each survey with Unique IDs

- Group questions into modules

- Write an introductory script for each module, to guide the flow of the interview. For example: Now I would like to ask you some questions about your relationships. It’s not that I want to invade your privacy. We are trying to learn how to make young people’s lives safer and happier. Please be open because for our work to be useful to anyone, we need to understand the reality of young people’s lives. Remember that all your answers will be kept strictly confidential.

- All questions should have pre-coded answer options. Answer options must:

- Be clear, simple, and mutually exclusive

- Be exhaustive (tested and refined during the Survey Pilot)

- Include 'other' (but if >5% of respondents choose 'other', answer choices were insufficiently exhaustive)

- Include hints to the enumerator as necessary. These hints are typically coded to appear in italics to clarify that they are not part of the question read to the respondent.

- For example: "For how many months did you work in the last 12 months? Enumerator: if less than 1 month, round up to 1.

Related Pages

Click here for pages that link to this topic.

Additional Resources

- Grosh and Glewwe’s Designing Household Survey Questionnaires for Developing Countries: Lessons from 15 Years of the Living Standards Measurement Study

- Dhar’s Instrument Design 101 via Poverty Action Lab

- McKenzie’s Three New Papers Measuring Stuff that is Difficult to Measure via The World Bank’s Development Impact Blog

- Lombardini’s measuring household income via Oxfam

- Zezza et al.’s Measuring food consumption and expenditures in household consumption and expenditure surveys (HCES)

- DIME Analytics’ Survey Instruments Design & Pilot

- DIME Analytics’ Preparing for Data Collection

- DIME Analytics’ Survey Guidelines

- DIME Analytics’ SurveyCTO slides

- DIME Analytics’ guidelines on survey design and pilot